Passion Devotion in Books of Hours

Authored by Cynthia Turner Camp

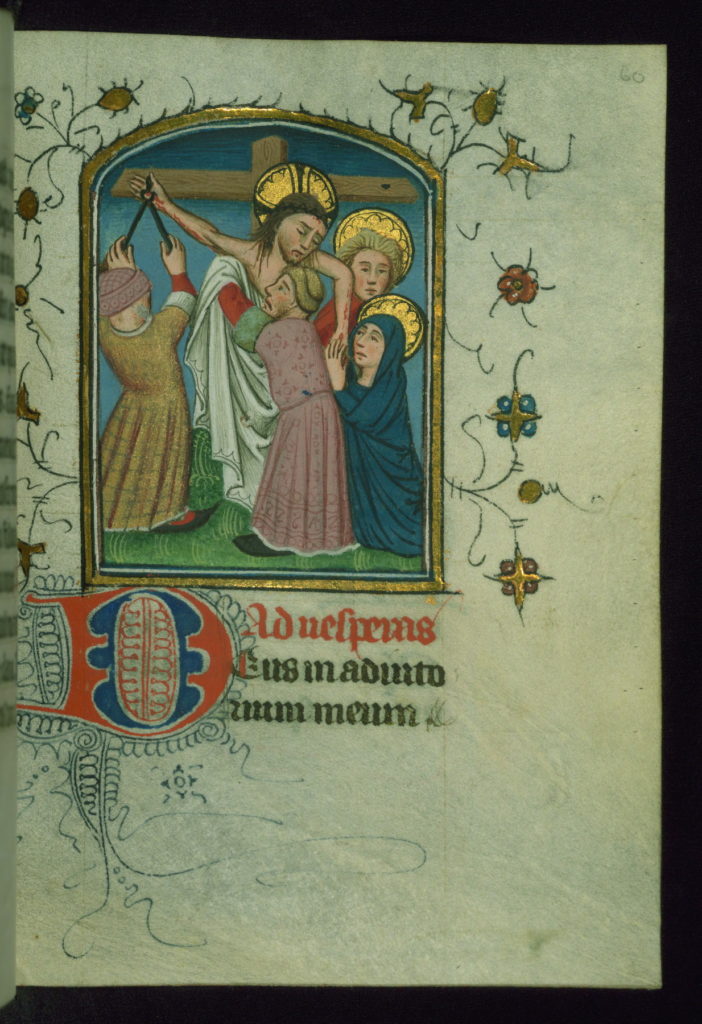

Baltimore, Walters Art Gallery MS W.164, fol. 60r. The Deposition from the Cross, opening Vespers of the Long Hours of the Passion

While the death and resurrection of Jesus has always been at the heart of Christian beliefs, the later medieval period saw interest in the suffering of Christ on the cross intensify. Most passion devotion was deeply imaginative and emotionally evocative. Following on the influence of the Pseudo-Bonaventuran Meditationes Vitae Christi (Meditations on the Live of Christ), many medieval texts on the Passion encourage their readers to envision themselves present at the Crucifixion. Immersing themselves in the story, readers are to feel compassion for Christ’s suffering so that they will become contrite, repenting of their sins for which Christ endured such pain (Baker 85-87). Such an emphasis on Jesus’s suffering also emphasized the humanity that both Christ and believers shared within the drama of salvation history (Duffy 235-37).

Books of Hours have often been characterized as objects of Marian devotion (Duffy 256, Scott-Stokes 1). This is undoubtedly true; the Hours of the Virgin define the genre, and both popular and rare prayers to the Virgin Mary appear in every Book of Hours. However, Books of Hours also frequently contain Passion-themed content. An extensive survey of digitized Books of Hours undertaken by students in 2017 revealed that, of the 217 manuscripts examined, seventy-six — that’s a third — of them contained at least one Passion-related text that also appears in the Hargrett Hours. More undoubtedly contained other Passion prayers and devotions. The late medieval fixation on the sufferings of Christ therefore permeated Books of Hours, making these ubiquitous prayerbooks a valuable witness to the breadth and variety of Passion devotion.

The prayers and devotions to the Passion present in Books of Hours provide a welcome balance to the kinds of Passion materials frequently studied by scholars. Most scholarship on Passion material focuses on narrative accounts of Jesus’s life and death or the dramatic examples within a textual tradition. These narratives and outliers frequently ramp up the emotionally charged, visually compelling potential of the Passion story with the goal of eliciting the reader’s intense pity and spiritual remorse. But not all Passion texts encourage the kinds of emotive reactions that Margery Kempe, for instance, famously experienced when she contemplated Christ’s death. While prayers in Books of Hours can dwell upon the brutal torture of Christ’s body (as does Hargrett Hours’ French Prayer 4), they more frequently don’t. Referencing but not elaborating upon the horrors of the Passion, these prayers encourage meditation through the formal, rhetorically balanced language of the liturgy. They rely upon apostrophe and are frequently structured through anaphora, homoioteleuton, and other figures of repetition, creating a rhythmic soundscape of contemplation. These devotions are also constructed out of biblical and liturgical language, either by importing passages from the Gospels or Psalms or simply by sampling memorable phrases. When we remember that many lay readers would have had limited comprehension of the prayers’ Latin words, the power of sound — the cadence of liturgical language and the familiar biblical phrases spoken aloud or even muttered under the breath — may help explain the continued comfort that medieval readers took from these prayers.

This Passion-themed content can take many forms, both textual and visual. Some of the most common textual Passion materials are the bonus Hours that frequently appear in Books of Hours: the Hours of the Cross and the Short Hours of the Passion. These are modeled on the Hours of the Virgin, in that they are a series of short readings and prayers to be said at different times of day, often appearing right after or integrated within the Hours of the Virgin (Wieck 89-91). The hymns that structure the Hours of the Cross, in particular, walk the reader through the events of Christ’s Passion, each canonical Hour becoming a meditation on the spiritual significance of that event (McCullough Table 11.1). More rarely, the Long Hours of the Passion may appear; this is a full-length office, equivalent to the Hours of the Virgin. While the Long Hours of the Passion normally appears alongside the Hours of the Virgin, in a few manuscripts it takes the place of the Hours of the Virgin.

Another possible Passion section is the Gospel accounts of the Passion. Most Books of Hours include short extracts from the four New Testament Gospels, known as the “gospel lessons” or “pericopes”; these extracts tell the story of Jesus’s life, from God’s divine plan as stated in John 1:1-14 through the Ascension. However, owners would occasionally include the biblical story of the Passion as well. Owners had three options to choose from. They could include a gospel harmony of the Passion, the full story of the Passion and Crucifixion from John 18-19, or (more rarely) the Passion accounts from all four Gospels. The decision to include the Gospel account of the Passion, whether from John or in harmony form, witnesses an interest in the narrative of Jesus’s passion and death, and is the only way that the Passion occurs as narrative in Books of Hours.

Whereas the Gospel account of the Passion provides the story of Jesus’s death, Passion prayers allow their readers to meditate on different spiritual facets of his suffering. Some, like the French Prayer 4 in the Hargrett Hours, might emphasize Jesus’s bloody, broken body as a way to elicit contrition. Others (like Hargrett Hours Prayer 3 and Prayer 6) list Jesus’s torments as a litany of persecutions in order to invoke his aid for both eternal salvation and earthly protection (Scott-Stokes 66-68,73-75). Others yet, frequently adaptations of the Hours of the Cross, may be a poetic, meditative recounting of the Biblical Passion story (Scott-Stokes 46-47; Barratt 272-73). Specific categories of Passion prayers also occur: meditations on Jesus as the the Man of Sorrows; prayers to Christ’s wounds or the Veronica (a cloth imprinted with Jesus’s face); devotions on the arma Christi, the implements of the Passion; and most expansively, the Fifteen Oes attributed to St. Brigitta of Sweden (Duffy 238-40, 249-55; Denny-Brown and Cooper; Krug). Some devotions may be more evocative than directly referential; the Psalter of the Passion, a sequence of Psalms, is only Passion-centric insofar as medieval Christians believed Christ to have said these Psalms from the cross. Even prayers that did not dwell on the Passion might use Jesus’s words from the cross as a way for the pray-er to orient their own spirituality or as a means of petitioning Jesus’s grace.

The Passion was, however, most commonly encountered pictorially. Miniatures representing the stages of the Passion and the Crucifixion might appear at several different places in a Book of Hours: opening the Hours of the Cross or Passion, prefacing the Gospel account of the Passion, or even introducing each hour in the Hours of the Virgin (Wieck 89-92, 104, 66-71). These miniatures are both narrative (in that they represent one moment in the Passion story, and often occur as a cycle of image, from the Agony in the Garden through the Entombment) and contemplative (in that they encourage the viewer to dwell devotionally upon the trials undergone by Jesus). Other Passion related miniatures may appear as non-narrative contemplative images, such as Jesus as the Man of Sorrows, the Arma Christi, or disembodied figures of Christ’s wounds. These miniatures represent different devotional ideas within the landscape of Passion devotion, encouraging meditation upon spiritual concept rather than historical event.

For many users of Books of Hours, the miniatures would have been the primary portal into a devotional mindset, the Passion being encountered first visually and secondarily verbally. Even in Books of Hours without miniatures, like the Hargrett Hours, the prayers may have been partially processed via the memory of Passion images. Readers’ wide experience of popular images like the Crucifixion, with Jesus on the cross and Mary and John standing to each side, or the Man of Sorrows, with Jesus bound and bleeding, the Crown of Thorns on his head, would have shaped their encounter with the text, guiding them visually through through a familiar devotional experience.

The Passion of Christ, as meditated upon via Books of Hours, would therefore have been a multisensory, visual and aural experience. While the emotions and imagination would have been engaged, as was true of other modes of Passion devotion, the way Books of Hours were used would also have compelled the readers’ eyes, ears, tongue, and lips to devotional service.

Bibliography

Baker, Denise N., trans. “The Privity of the Passion. Cultures of Devotion: Medieval English Devotional Literature in Translation, ed. Anne Clark Bartlett and Thomas H. Bestul, Cornell UP, 1999. 85-106.

Barratt, Alexandra. “The Prymer and its Influence on Fifteenth-Century English Passion Lyrics.” Medium Aevum vol. 44 (1975), 164-79. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43628137.

Denny-Brown, Andrea, and Lisa Cooper, eds. The Arma Christi in Medieval and Early Modern Material Culture: With a Critical Edition of ‘O Vernicle’. Ashgate, 2014.

Duffy, Eamon. The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England c 1400-c. 1580, Yale University Press, 1992.

Krug, Rebecca, trans. “The Fifteen Oes.” Cultures of Devotion: Medieval English Devotional Literature in Translation, ed. Anne Clark Bartlett and Thomas H. Bestul, Cornell UP, 1999. 107-117.

McCullough, Eleanor. “‘Thenke we sadli on his deeth’: The Hours of the Cross as a Short Passion Meditation.” Devotional Culture in Late Medieval England and Europe: Diverse Imaginings of Christ’s Life, ed. Stephen Kelly and Ryan Perry, Brepols, 2014. 385-404.

Scott-Stokes, Charity, ed. and trans. Women’s Books of Hours in Medieval England: Selected Texts, D.S. Brewer, 2006.

Wieck, Roger. Time Sanctified, George Brazillier, 1988.