One of the most compelling aspects of our research into the suffrages was learning about the saints contained within the Hargrett Hours. We have an extensive list of forty men and women, so Grace used David Farmer’s Oxford Dictionary of Saints to get some baseline information on all of them. From there, she chose a few distinctive saints to see what information they could give us on when and where the Hargrett Hours was made. One saint in particular stood out. In a section of more recognizable saints like Nicholas and Augustine of Hippo, we found Fiacre. Farmer notes that Fiacre was the patron saint of gardeners and those who suffer from STI and he was also a misogynist. Why did this guy merit a suffrage in the Hargrett Hours? Was he a common figure in Paris and just lost to time? Fiacre became a clear contender for further research.

Who was this guy? Fiacre lived during the 7th century, but accounts of his life didn’t really show up until the 9th century, and even then, his legend doesn’t become too popular until the 13th. In an article published in Modern Language Quarterly, medieval scholars M.E. Porter and J.H. Baltzell describe several 15th century texts that provide accounts of Fiacre’s life. They tell us Fiacre was the son of an Irish nobleman and spent his early life studying theology to try to emulate the saints. When he became an adult, his father demanded that Fiacre should marry. Fiacre refused, saying that he made a vow of virginity. Unable to resolve this disagreement, Fiacre fled the country and went to Meaux, France, a small town northeast of Paris. There, he met the bishop Faro and worked as his secretary. Eventually, the bishop granted Fiacre a plot of land where he built a small chapel and hermitage. He became known as a miracle worker and healer and lived into old age (Porter Baltzell 21, 24-25).

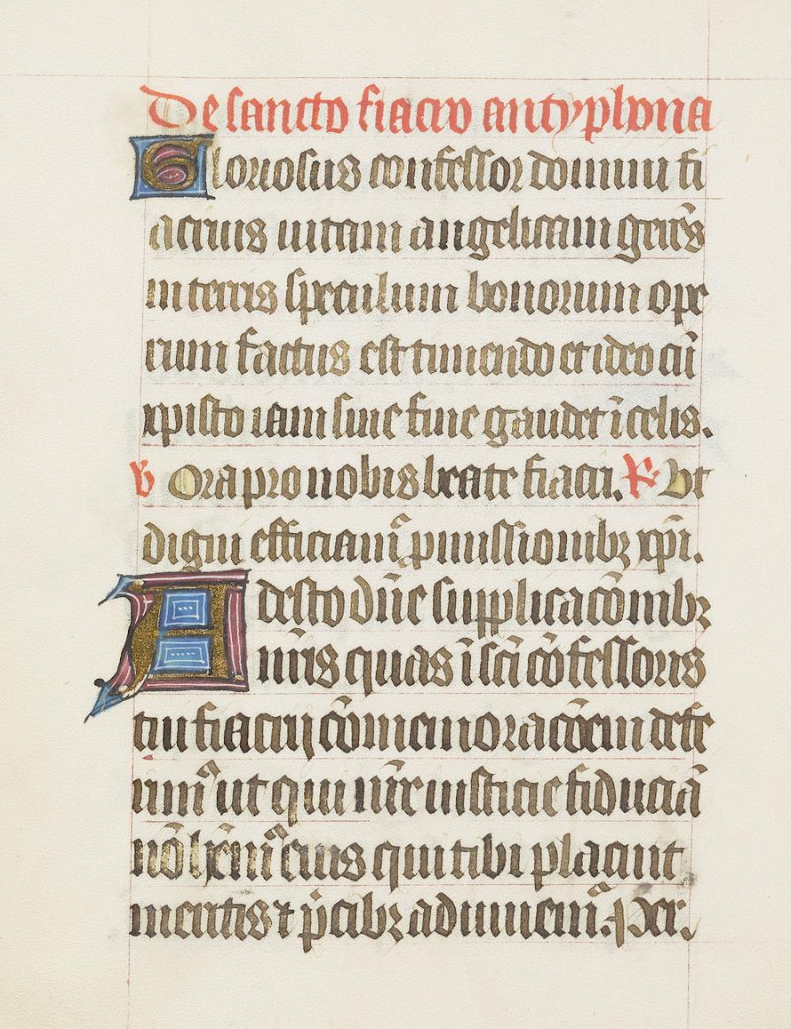

Though he was an Irishman, it turns out that Fiacre was pretty popular in Paris around the time in which Hargrett Hours was made. In our research, we found examples of suffrages to Fiacre in at least three other use of Parisian books of Hours, including Kislak Center for Special Collections, Ms. Codex 2030 pictured below. We also discovered that Fiacre’s cult grew in popularity during the 12th century due to the distribution of his relics and the patronage of the nobility, such as Louis IX (Picard 422-423). By the 15th century, his cult was well established in Paris. Fiacre’s inclusion in this manuscript confirms that the book was likely made in Paris in the 15th century.

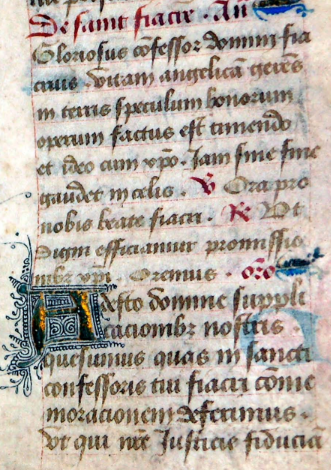

Fiacre’s suffrage in the Hargrett Hours Fiacre’s suffrage f. 74v

Kislak Center for Special Collections, Ms. Codex 2030 Fiacre’s suffrage f. 100v

Fiacre’s suffrage in the Hargrett Hours is vague. It doesn’t mention any specific miracles that Fiacre performed. This would have been something someone using this book would have already been familiar with, so there is no need to include it in this simple prayer. It includes the typical request for Fiacre to pray for the owner of this manuscript. This ties into the medieval view of saints as intercessors between normal people and God.

According to Jean-Michel Picard, who wrote an article about Fiacre’s cult in France, during the time of the Hargrett Hours, Fiacre was known primarily as a healer (Picard 422). As a saint, he specialized in blood diseases, skin diseases, and malign growths, most notably hemorrhoids. In French, colloquial terms for hemorrhoids are le fic Saint Fiacre (ficus of saint Fiacre) or le mal Saint Fiacre (St Fiachra’s ailment) (Picard 422). There are many stories about Saint Fiacre relating to hemorrhoids, both as a curer and causer. One notable story tells of Geoffroy de la Chapelle, a high official at the court of the French king, Saint Louis, who was cured of a fic after visiting Saint Fiacre’s shrine. Another story says that when King Henry V came to France to steal Saint Fiacre’s remains, the long-dead Saint caused him to die from hemorrhoids or dysentery (Bonello Demchuk 45-46).

Statue of Saint Fiacre, The Met

Today, if you Google “Fiacre”, most of what you will find emphasizes him as the patron saint of gardeners. While this wasn’t as popular as his perception as a healer, it was a part of his image during the 15th century. One legend says that he was able to instantly dig a trench by dragging his staff in between two trees. During this process, God transformed Fiacre’s staff into a spade (Bonello Demchuk 44). Fiacre is typically depicted with this spade in art, as seen in the picture on the left. While this is an entertaining story, his patronage of gardeners probably ties into the fact that his treatments for hemorrhoids were medicines derived from plants. If you look into the typical method for treating hemorrhoids during the 15th century (Google at your own risk), it’s clear to see that it would be pretty miraculous to have an alternative option!

Saint Fiacre is a very well known misogynist. The legend goes that a woman once accused Fiacre of witchcraft. In response, the saint sat on a stone; as long as he was seated on it, the stone became soft, creating an indentation (see photo). To the people of the time, this miracle proved that he was a man of God, not a practitioner of magic. He then prayed that no woman ever be allowed into his church, which was proven to be another miracle when a woman attempted to enter and immediately went blind in one eye. (Bonello Demchuk 44) Even in death his misogyny meant that women, who would come to his tomb to pray for help with problems of menstruation and fertility due to his specialization in blood disease, were not allowed to enter the actual sanctuary (Picard 422).

Thor19, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

One of the most fascinating elements of St. Fiacre’s legend was the emphasis on him as a virgin. While male saints can fall into three categories of apostle, martyr, and confessors, all female saints fall into the category of virgin. While that doesn’t reflect the sexual activity of all these women, usually their sexuality plays an important part in their legends. In our survey of saints, there were no other discussions of male sexuality. It’s also interesting to note that he’s specifically called a “virgin,” since typically men who were sexually inactive for religious reasons were called “celibate.” Kathleen Coyne Kelly discusses male virginity in her book Performing Virginity and Testing Chastity in the Middle Ages. She states that while there were other accounts of male virginity, they were uncommon. She attributes this to the fact that these stories challenge the norms of a patriarchal society. In these stories, the woman is the one pursuing, while the man is the one being pursued (Kelly 99). This feminizes the men of these stories and challenges the idea of women as the weaker sex.

The emphasis on male virginity is seen in the 16th century play that Edward Gallagher calls the 1529 Fiacre. Prior to this play, several 15th century plays focused on Fiacre’s life in France and his miracles. In contrast, the 1529 Fiacre only talks about our saint’s life in Ireland before he flees to France. In this play, Fiacre defends his vow of virginity through debate with allegorical figures sent from Satan. In these debates, he goes as far as to reject the idea of marriage altogether. In previous accounts, Fiacre seems uninterested in women, but in this play the woman Fiacre’s father wants him to marry genuinely tempts Fiacre. While he is able to maintain his vow of virginity, he struggles and has to flee the country to guarantee he won’t be tempted again (Gallagher 333-343).

But why should we care about this guy? Sure, he has an entertaining legend, but do we get anything else out of this? Absolutely! Saints were kind of like the medieval version of superheroes- they’re larger than life figures that are capable of incredible feats. Medieval people were so drawn to Fiacre’s ability as a healer that they believed he could also act as a powerful intercessor between them and God. The text of our suffrage suggests that this is how the owner of the manuscript viewed him. However, the appeal of some saints is that they were normal people that could be imitated. This shift began in the 16th century and elements can be seen in the 1529 Fiacre play. This play gave medieval people a model for resisting sexual temptation.

By looking at more obscure saints in Books of Hours, we can find out more about the specific person who commissioned the manuscript, but the more popular ones can tell us what society as a whole values. It turns out that Fiacre was pretty popular in Paris during around the time the Hargrett Hours was made. Through his life as a healer, we can see the value for selflessness in service to others. We also see the medieval preoccupation with virginity, that doesn’t seem to just relate with women’s virginity.

If all of this information can be gleaned from just one of the saints in the suffrages, imagine the wealth of knowledge that we could learn by researching every part of this Book of Hours. There is a story hidden in the Hargrett Hours, behind the prayers and the calendar, behind the parchment and the binding, behind every one of the saints: we just have to know where to look.

Grace Deaton and Anya Ricketson, with translation by Zack Dow for Team Suffrages (Mounawar Abbouchi, Kristina Durkin, Rachel Menikoff)

Works Cited

Bonello, Julius, and Carley Demchuk. “St Fiacre: The Patron Saint of Hemorrhoid Sufferers.” History Magazine, vol. 19, no. 6, Aug. 2018, p. 43. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,shib&db=edsggo&AN=edsgcl.549577049&site=eds-live.

Farmer, David Hugh. The Oxford Dictionary of Saints. Oxford University Press, 1997. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,shib&db=nlebk&AN=12301&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Gallagher, Edward J. “Saint Fiacre in Early Sixteenth-Century Paris: The 1529 Drama of His Life Before Meaux.” Neuphilologische Mitteilungen, vol. 109, no. 3, 2008, pp. 331–46. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43344365. Accessed 6 Nov. 2023.

Kelly, Kathleen Coyne. Performing Virginity and Testing Chastity in the Middle Ages, Taylor & Francis Group, 2000. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ugalib/detail.action?docID=178659.

Picard, Jean-Michel. “Hagiography and Folklore: The Cult of St. Fiachra in France.” Sean, Nua Agus Síoraíocht: Féilscríbhinn in Ómós Do Dháithí Ó HÓgáin, edited by Ríonach uí Ógáin et al., Coiscéim, 2012, pp. 418–35. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,shib&db=mzh&AN=2022243156584&site=eds-live.

Porter, Marion Edward, and J. H. Baltzell. “Medieval French Lives of Saint Fiacre.” Modern Language Quarterly, vol. 17, Mar. 1956, pp. 21–27. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.1215/00267929-17-1-21.

Saint Fiacre. 15th Century. Alabaster. The Cloisters Collection, New York. The Met, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/472307. Accessed 2023.

Thor19, Saint-Fiacre church 4.jpg. 2013. Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Saint-Fiacre_%C3%A9glise_4.jpg?uselang=fr