The list of suffrages to saints in a Book of Hours are like the owner’s favorite musicians: those saints can tell us about the owner’s devotional practice. Maybe they only listen to the Top 40 with saints like Peter, John the Baptist, and the Virgin Mary. Maybe they are ride or die for one artist — like the owner of Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS Latin 1183 with only one suffrage to Eutrope. Or maybe you’re the owner of the Hargrett Hours and listen to a bit of everything.

The owner of the Hargrett Hours venerated many different “genres” of saints — the Twelve Disciples, medical saints, and the niche reformed prostitute.

You may hear “reformed prostitute” and immediately draw the connection to Mary Magdalene. So did the owner of the Hargrett Hours! In her medieval legend, Mary Magdalene was a combination of three biblical women — the woman actually named Mary Magdalene that had seven devils exorcized from her; Mary of Bethany, who was the sister of Lazarus and Martha; and the unnamed prostitute that anointed Jesus’ feet (Reames).

Mary Magdalene, despite being from a more niche genre, was a really popular saint in Books of Hours. Most people don’t need to go further than Mary Magdalene for all their reformed prostitute needs, but the owner of the Hargrett Hours wanted one more — just in case!

Enter Mary of Egypt, a saint whose legend dates back to the fifth century and who was — you guessed it — a reformed prostitute. Her legend states that she fell into a life of sin and was a prostitute for 17 years. She joined a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, but was unable to enter a church. She received a vision from the Virgin Mary that convinced her to repent. After her conversion, she lived as a hermit in the desert until the end of her life, where she died as a virgin (Cazelles).

Now that the owner of the Hargrett Hours has picked their favorite saints, it’s time for them to choose their favorite songs by these artists — the actual text of the suffrages. The text of a suffrage includes an antiphon, versicle and response, and a prayer, but we’ll just be looking at the antiphon. Anderson describes antiphons as “short liturgical chants with a prose text” (Anderson 36). Most of the time, suffrage antiphons come from a larger liturgical service book that contains many different antiphons for one saint. Since suffrages usually only contain one antiphon, it’s important to pick an antiphon that really encapsulates the element of the saint that you want to invoke when you’re saying your suffrage (Anderson 163). Let’s look at what texts the Hargrett Hours include.

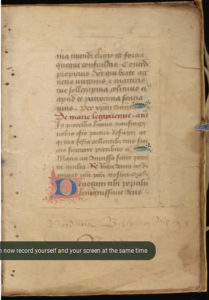

In the Hargrett Hours, Mary of Egypt appears first and the owner chose this antiphon:

In procellis hujus naufragii nobis esto portus Refugii atque tua festa collentibus tuis sanctis succurre precibus.

In the storms of this shipwreck, be a port of refuge for us, and help those who worship your feast with prayers. (Translated by Mounawar Abbouchi)

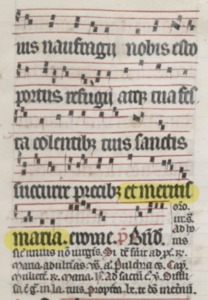

This text seems to be an allusion to French vernacular legends, where Mary of Egypt is voyaging from Alexandria to Jerusalem. During this voyage, Mary of Egypt seduces every man on the ship while there is a storm raging. Despite her depravity and the storm, Mary does not fear for her safety, spiritual or physical. This is typically the most detailed depiction of Mary’s sin in the French vernacular legends, so the antiphon really wants to hammer home the fact that Mary is a sinner (Cazelles). Additionally, this antiphon “flips” Mary’s act of sinning in the storm to invoking her to save the person praying from metaphorical or spiritual storms. By referencing this text in particular, we gain some insight into what texts the owner of the Hargrett Hours was engaging with. The only liturgical manuscript that this antiphon shows up is the c. 1300 Notre Dame breviary ((Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS Latin 15181), which suggests that this text is unique to Paris. The owner of the Hargrett Hours must have been pretty in tune with the local Parisian music scene.

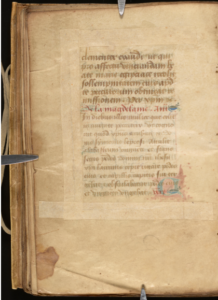

Mary Magdalene is up next, with the antiphon:

In diebus illis mulier que erat in civitate peccatrix. Ut cognovit quod Christus accubuit in domo symonis leprosi attulit alabastrum unguenti et stans secus pedes domini nostri Jesu Christi lacrimis cepit rigare pedes ejus et capillis capitis sui tergebat (et) obsculabatur pedes eius et unguento ungebat.

In those days there was a woman that was in the city, a sinner, who, when she knew that Christ sat at meat in the house of Symon the Leper, brought an alabaster box of ointment. And standing behind at the feet of our lord Jesus Christ, she began to wash his feet, with tears, and wiped them with the hairs of her head, and kissed his feet, and anointed them with the ointment. Luke 7:37-38 (Douay-Rheims Bible)

While this text defines Mary Magdalene as a sinner, it focuses more on her actual act of penance. It is also the previously mentioned text where Mary Magdalene is not explicitly named, but where the penitential action is attributed to her. This text also comes directly from the Gospels, a choice that emphasizes her as a biblical saint. Not only is the antiphon directly from the Gospels, it is also a broad and universal antiphon. It appears not only in French breviaries, but in liturgical manuscripts from all across Europe, making the text one of Mary Magdalene’s greatest hits.

Interestingly, the antiphon to Mary of Egypt also doesn’t name her. In the Hargrett Hours, most of the saints are named in their antiphons. The only exceptions are biblical figures whose antiphon are coming directly from the Gospels or referencing it. The original text of Mary of Egypt’s comes from the c. 1300 Notre Dame breviary, and that antiphon ends with the phrase “et meritis maria” or “and the merits of Mary” (pictured to the left with additional text highlighted). While this omission could just be due to the scribe not having access to the full antiphon, it’s interesting that both antiphons leave the women unnamed. The owner of the Hargrett Hours seems to want to draw a connection between these two women, since they appear directly next to each other in the suffrages. In suffrages, there is a hierarchy of categories of saints — apostles, martyrs, confessors, and virgins — but there isn’t a set order within these categories. For example, in two other Parisian manuscripts that contain both Mary of Egypt and Mary Magdalene, they appear pretty far away from each other. The owner of the Hargrett Hours placing these two women next to each other seems to be a deliberate choice to emphasize their similarities

Mary of Egypt and Mary Magdalene both being unnamed in their antiphons makes them easier for the person praying to relate to. In most cases, a medieval person would not put themselves on the same level as a saint. However, it’s easier to associate with these women because they are defined as people who sinned, but were able to reform and gain God’s forgiveness. While the owner of the Hargrett Hours wouldn’t aspire for sainthood, these women make forgiveness more achievable.

– Grace Deaton

Works Cited

Anderson, Michael Alan. Music and Performance in the Book of Hours. Routledge, 2022.

Cazelles, Brigitte. The Lady As Saint : A Collection of French Hagiographic Romances of the Thirteenth Century, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1991.

Reames, Sherry L. “The Legend of Mary Magdelen, Penitent and Apostle: Introduction.” Middle English Legends of Women Saints. Medieval Institute Publications, Western Michigan University, 2003. https://d.lib.rochester.edu/teams/text/reames-middle-english-legends-of-women-saints-legend-of-mary-magdalen-introduction

Manuscripts Consulted

Bibliothèque nationale de France Latin 1183

Bibliothèque nationale de France Latin 15181

UGA Hargrett Library Hargrett MS 836