Her [Genevieve’s] guardianship of Paris meant that Parisian men accepted a female patron. While many cities and countries (including France itself) put themselves under the patronage of the Virgin Mary, it was rare for a city, let alone a major city like Paris, to assume a totally human female saint as protectoress.”

Patroness of Paris by Mary Sluhovsky

Sainte Geneviève, patronne de Paris, devant l’Hôtel de Ville; à droite, les Huns repoussés, vers 1620. 1615-1625. Musée Carnavalet, https://www.parismuseescollections.paris.fr/fr/musee-carnavalet/oeuvres/sainte-genevieve-patronne-de-paris-devant-l-hotel-de-ville-a-droite-les

There are two groups of people who may have heard of Saint Genevieve – those who have been to Paris or those that are Catholic. I am not Catholic, and my two day stint in Paris did not leave me with any memorable encounters with Genevieve. So, if you are like me, you may be wondering why you should care about this saint? At first Genevieve did not stand out to me. That was until I found out that she was the Patron Saint of Paris. It immediately made me question why she was so popular in Paris when most medieval cities simply prayed to the Virgin Mary. Everything became more confusing when I read Genevieve’s translated prayer – instead of being about protecting the city, it was focused on healing. So who really was this woman? Why is she so revered in Paris? And where does the healing aspect come from?

Genevieve was born in Nanterre, France around 420. As a child, she stood out to a traveling Saint Germanus and was quickly consecrated. She really rose to prominence in 451 when, through the power of her prayers, she diverted the Huns from Paris and saved the city. This miracle was the first event that solidified Genevieve as a major religious figure in France. She continued to establish her position by healing the citizens of the country, curing them from blindness, paralysis, and, most famously, fevers.

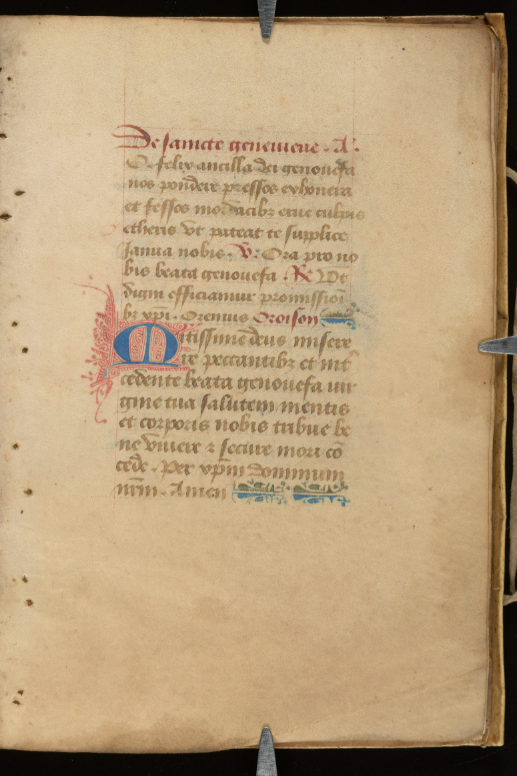

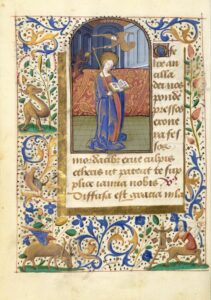

By the fourteenth century, Genevieve had become known as the patron and protector of Paris, on par with the Virgin Mary in the city’s eyes. Not only was she invoked by the common layperson, but Genevieve’s relics were also processioned through the city during times of crisis. As a result, she became a popular saint to include in Books of Hours made in and around Paris. The University of Georgia’s Hargrett Hours is no exception; it contains two days in its calendar dedicated to Saint Genevieve, and it contains a specific suffrage to this saint. The prayer is shown below; here it is in translation:

A: O happy handmaiden of God, Genevieve, relieve us, burdened, from our burdens and pluck our bitter faults from us, weakened, such that the door of heaven may open to us, we beg you.

V: Pray for us Saint Genevieve.

R: So that we may be made worthy of the promises of Christ. Let us pray.

O: Most gentle God, have mercy on the sinners and, by your interceding virgin Saint Genevieve, grant us health of mind and body, and allow us to live well and die free from care. By Christ our Lord Amen.

One would assume that a prayer to the protector of Paris would focus on saving the city and its people, but as we can see, this prayer does not mention her status as the Patron Saint. Instead, it focuses on Genevieve as a healer. While at first glance, this may seem odd, the emphasis on health actually aligns it with most of the suffrages for Genevieve from Paris. This prayer specifically focuses on Genevieve’s healing powers, asking for “the health of mind and body.”

In our research, we looked through 50 Parisian Books of Hours; 23 of them had suffrages to Saint Genevieve. This is a significant number, showing Genevieve’s popularity among Parisians and in their Books of Hours. These prayers can be broken into three different categories: first, a general and non-descript prayer to this saint (4 prayers); the second, appeals for help with rain, as she was invoked in times of famine and crop failure (1 prayer); and the third, appeals for health (18 prayers). Therefore, we can conclude that Saint Genevieve was not typically invoked because of her miracle of saving Paris, but instead was called upon during times of illness.

This prayer helps teach us what was important to medieval people of Paris. They clearly had a fear of sicknesses, but unfortunately, they had very little understanding of how to cure them. Therefore, it makes sense that they would try to do everything they could to make sure they stayed safe and healthy. When looking at the times Genevieve was invoked by the whole city, one can see that she was called upon and her relics carried through Paris several times to protect France during battles and wars or to protect against famines and floods (Sluhovsky 217-219). These large disasters were not very common, but sickness was, which means that people would not be praying about these large events on a daily basis. They would instead focus more on their own health and well-being, which is why Genevieve was a popular saint to include in Books of Hours.

Medical saints are actually more common than I originally thought, especially in the Hargrett Hours. Again, since there was little known about illnesses and how to treat them, medieval people relied on saints, like Genevieve or Saint Apollonia, to stay healthy. Genevieve’s suffrage in the Hargrett Hours can be interpreted many ways, but after looking through other prayers to Genevieve, it seems like in the author’s reference to “the health of mind and body,” they had well-being in mind. Specifically, the request for aid to keep the body healthy makes it seem like people were concerned about catching sickness and having physical reactions.

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Ms. 37, fol. 152v. Saint Geneviève. 1480 –

1490. Artstor, library.artstor.org/asset/AGETTYIG_10313915818.

Most importantly, these other suffrages show us the uniqueness of Genevieve’s prayer in the Hargrett Hours. Out of the 23 suffrages, seven of them exactly match the prayer in UGA’s prayer book. The Hargrett Hours’ suffrage to Saint Genevieve is not uncommon, but was being said throughout the city. But even though this is clearly a popular Parisian prayer, we can’t quite tell exactly where it comes from. Most suffrage antiphons and prayers that originated in Paris first appeared in liturgical books, breviaries, and missals. I originally expected Genevieve’s antiphon to be in the breviary of Notre Dame, the main church in medieval Paris, but it was not there. So we know the prayer was circulating around Paris somewhere, but we cannot yet pinpoint its source. This is important because we do not know where the Hargrett Hours originated. Although research has been done into which church this book could be affiliated with and what type of person would have owned it, it is still unclear. Hopefully, this information about Genevieve will help us answer this question. Until then, we at least know more about Saint Genevieve and that health is more important in prayers than we originally thought.

-Rebecca Haulk

Works Cited

Sluhovsky, Moshe. Patroness of Paris: Rituals of Devotion in Early Modern France. E J Brill, 1998.