Welcome to Personal Liturgical Calendars, where I dive into a comparison of two calendars from Parisian Books of Hours. The roller coaster of questions about personal liturgical calendars stem from the mystery of the Hargrett Hours calendar. When I call something personal and liturgical, it sounds contradictory. Yet, I stand here with a very confusing and contradictory calendar in the Hargrett Hours manuscript. My post is split into two parts (here’s Part 2), covering the grading of calendars and important ecclesiastical feasts of two major Parisian cathedrals.

First, we need to break down a calendar. We all know what our modern calendars look like; a medieval one is not so different. The medieval calendar still consists of a table of dates grouped into twelve months. Modern calendars are designed with a week-based grid, but the medieval calendars are perpetual. Essentially medieval calendars were designed to be used every year without alteration, so the dates appear in a list rather than a grid. In the medieval calendar, you will find religious holidays and saints’ feasts written in the individual days of the months, making the calendar one long list of saints and holidays.

The medieval perpetual calendar originated in a church context. Medieval liturgical calendars were created to help church leaders know when to celebrate the holy days. They show up at the beginning of manuscripts used during the church service, for example, in missals, breviaries, and psalters. Liturgical calendars also include abbreviated directions for how elaborate the church service for that feast should be. These directions, called “grading,” are added at the end of the line, after the name of the saint or feast, and they can range from “duplum” (the highest grading for the most important feasts, like the Circumcision of Christ) to “memoria” (the lowest grading, in which the priest simply adds some extra prayers for that saint to the day’s regular service).

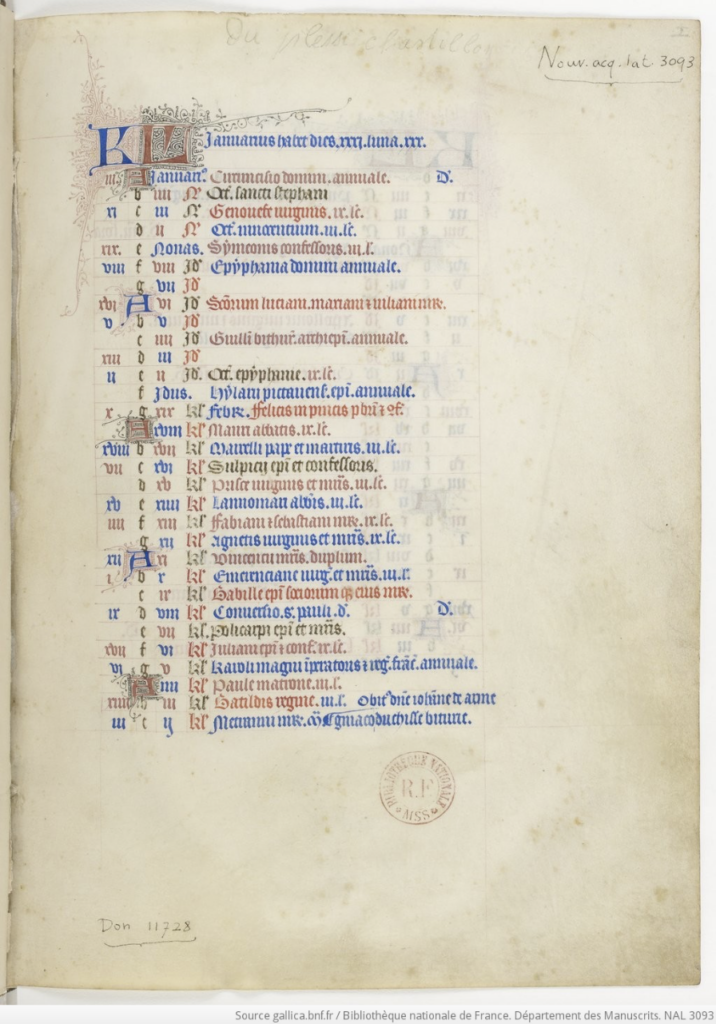

Figure 1. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS NAL 3093, fol. 1r, January. In this calendar, you can see that Vincent (written next to the third decorated A from the top) is graded “duplum,” However, Polycarp, four lines lower, has no written grading, signaling that he only gets a “memoria” grading.

Calendars also show up at the beginning of personal Books of Hours. The calendars in Books of Hours differ from liturgical calendars in two ways. First, most Parisian Books of Hours contain composite calendars: a calendar where saints’ feasts fill in every day. A liturgical calendar, on the other hand, includes ferial days (blank lines), days when the service does not honor a specific saint with extra prayers. Second, calendars in Books of Hours are typically not graded, and composite calendars are never graded; they are simply filled with the saints’ feasts. They lack the highly specific technicalities of liturgical calendars.

You may be asking, how can our calendar be an oxymoron if we have a Book of Hours? Wouldn’t it simply be a personal calendar? Wonderful question, because our research truly is one giant roller coaster. Each day brings a new twist and turn as our research evolves. My fellow researchers and I have studied and transcribed 70 calendars from Parisian Books of Hours. From this pool, only three Parisian personal prayer books contain calendars copied from liturgical calendars. The three outliers show that composite calendars are the norm for Parisian Books of Hours. The two out of three calendars that are the study of this blog both have ferial days and one includes liturgical grading, throwing us into a new twist of our roller coaster.

Now that our seats are locked and safety precautions read aloud, let’s get this ride going. We have two Parisian Books of Hours that need deciphering. Our two Books of Hours are UGA, Hargrett Library MS 836 (Hargrett Hours) and Oxford, Keble College MS 44 (the Keble calendar). The Keble manuscript came to me via a fellow researcher who transcribed the calendar while studying at Oxford University. In order to understand the Hargrett Hours calendar, it is important to understand the Keble calendar as well.

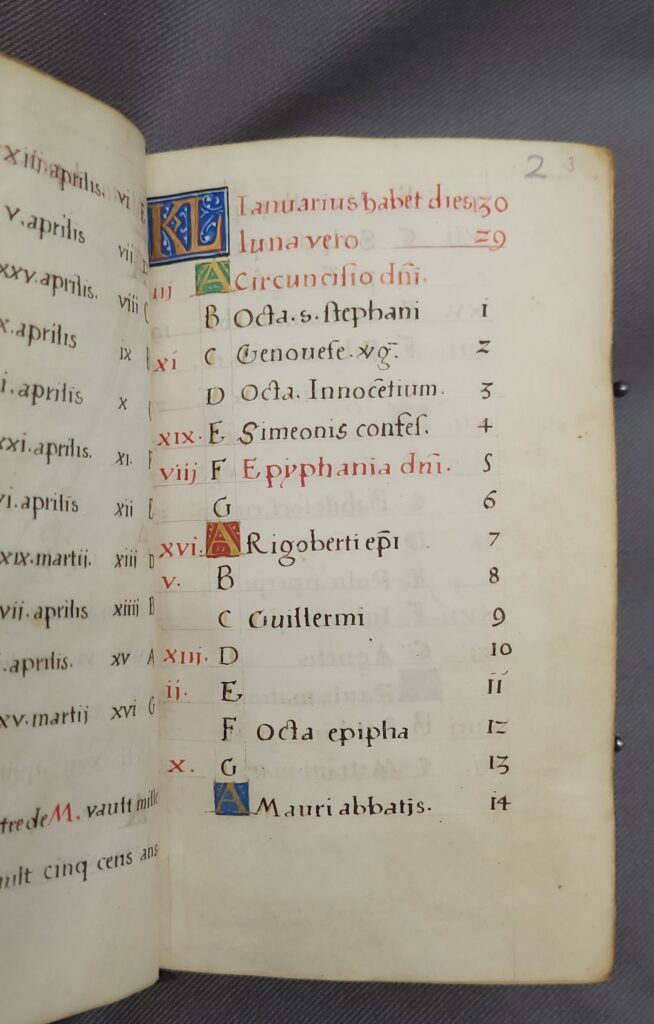

The Keble calendar provides a lot of information about the Hargrett Hours calendar. Yet, the calendars could not look more different from each other. The Hargrett Hours calendar was written in lettre bâtarde. The bookhand has elongated letters that come off as curly and has some unfamiliar letter forms. In the Keble calendar, the bookhand is a script recognizable to modern eyes (figure 2). This bookhand is referred to as humanistic and was created “as a conscious reaction against the Gothic scripts” (Clemens and Graham 175). Though these calendars look different, their grading and content both contain the necessary information in the search for the Hargrett Hours’ origin.

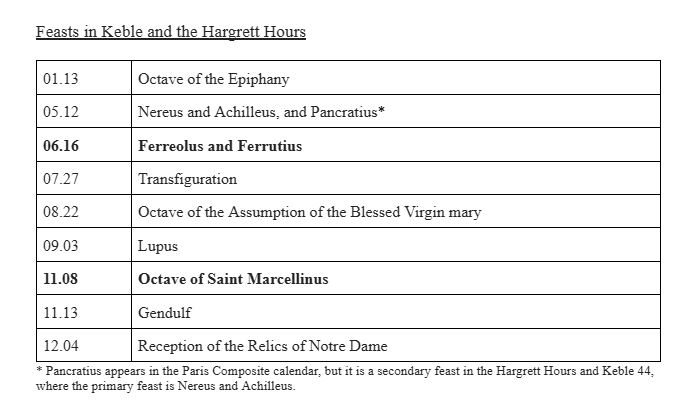

The Hargrett Hours and the Keble calendars contain quite a few feasts that don’t appear in Paris composite calendars, but do show up in Parisian liturgical calendars from Notre Dame Cathedral and Ste-Chapelle. Overall, Hargrett Hours and Keble share nine feasts that are not common in the Paris composite calendars (Table 1).

The 16 June and 8 November feasts are only found in the Hargrett Hours and the Keble calendar. These two feasts are a part of a grouping of feasts that are only found in the Hargrett Hours calendar. The two anomalous feasts represent the rarity of the Hargrett Hours and Keble calendars. While these two saints lead to more questions, other saints in the Keble and Hargrett Hours calendar establish links to liturgical calendars of Notre Dame and Sainte Chapelle. An example includes the 13 November feast, in which Saint Gendulf, a bishop of Paris and confessor (a classification of saints) is honored during service. In the Paris composite calendars, Saint Brictius is the most common saint. Saint Gendulf appears primarily in Notre Dame and Ste-Chapelle liturgical calendars.

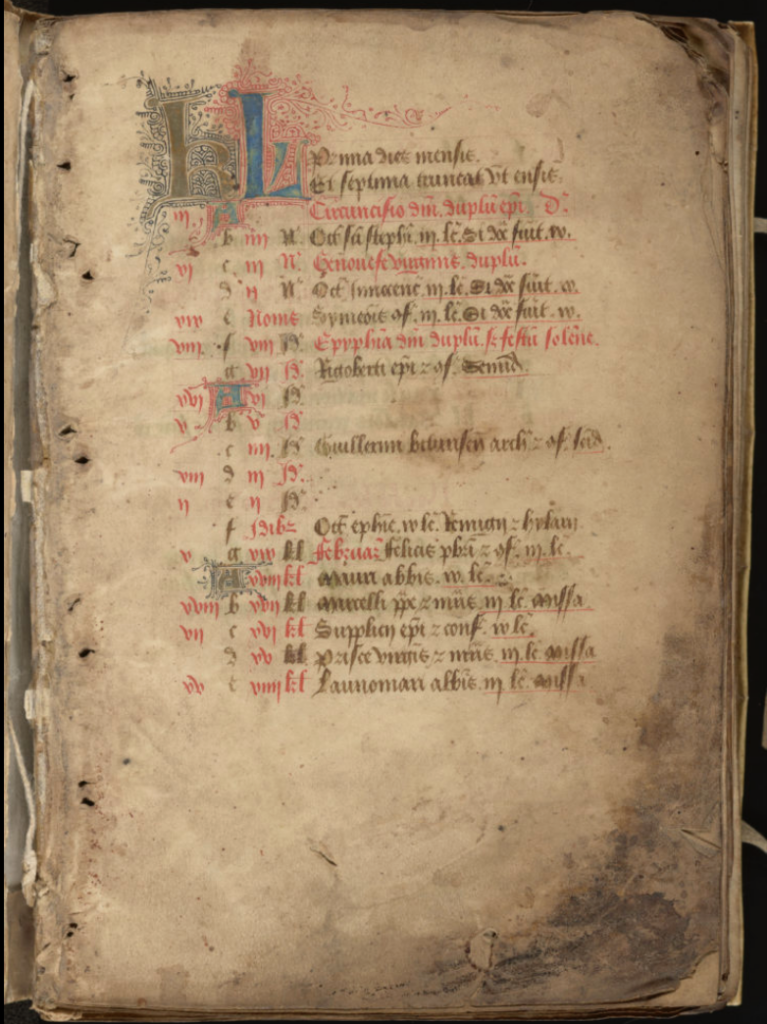

Figure 3. UGA, Hargrett Library MS 836, fol. 1r, January. Note the written grading added to the ends of each line.

In the Hargrett Hours’s calendar (figure 3), grading follows the saint, which is common in liturgical calendars. The feast on January 1st, Circumcision of Christ, appears in red ink. The grading itself is “duplum episcopi,” signaling that this feast day is of utmost importance. The red ink emphasizes the feast: “in most calendars the majority of feasts were written in black ink… whereas the important feasts appeared in red” (Wieck 2). The Hargrett Hours therefore utilizes two forms of grading.

Now, looking at figure 2, we see that the Keble calendar does not have the written grading. Instead, the calendar’s scribe used ink colors to create hierarchy. In the Keble calendar, both the Circumcision and the Epiphany are written in red. Although composite calendars are also multi-colored, those colors are instead often “false grading,” color used for effect rather than to signal liturgical opulence (Wieck 3). The scribe of the Keble calendar did take the time to color grade the calendar, but the manuscript owner did not need the technical liturgical grading that we see in the Hargrett Hours.

To find out more about our calendars, continue on to my Personal Liturgical Calendars Part 2. There we will take the drop into the feasts of our two calendars.

— Authored by Rachel Warner

Works Cited

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS NAL 3093.

Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 2007.

Oxford, Keble College, MS 44

University of Georgia, Hargrett Library, Hargrett MS 836

Wieck, Roger S. The Medieval Calendar: Locating Time in the Middle Ages. New York, Scala Arts Publishers, Inc., 2017.

Websites consulted:

Macks, Aaron. CoKL: Corpus Kalendarium, 2016-2024. http://www.cokldb.org/. Accessed 27 Apr. 2024.