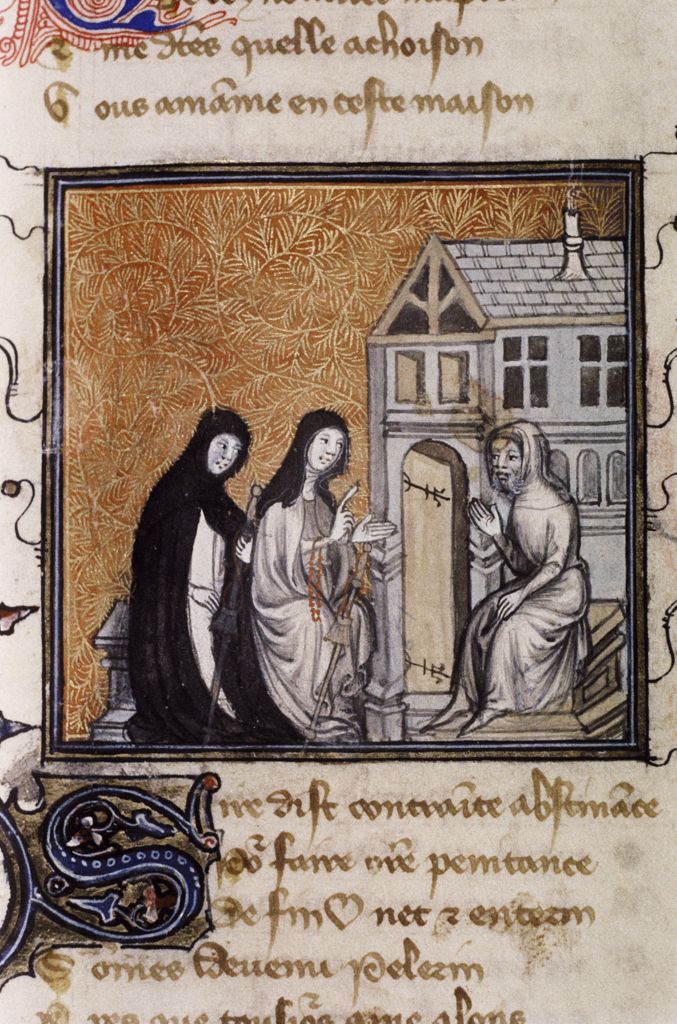

Print of a Beguine in Des dodes dantz of Matthäus Brandis, Lübeck 1489.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beguines_and_Beghards

Beguines were a unique or as some may say “underground” or “indie” group of religious women who were prevalent in later medieval Europe. In the Fall semester of 2023, I decided to conduct research on beguines in Paris and their relationship with books; this research can be found here. I conducted this research to determine who may have owned the Hargrett Hours. However, there is little extant evidence of beguine-owned books in Paris. So, in a restless pursuit to determine a plausible owner of the Hargrett Hours, I delved more into the relationship of beguines and their books outside of Paris. My new deep dive in the Spring semester took me straight to Mary of Oignies, the original beguine herself.

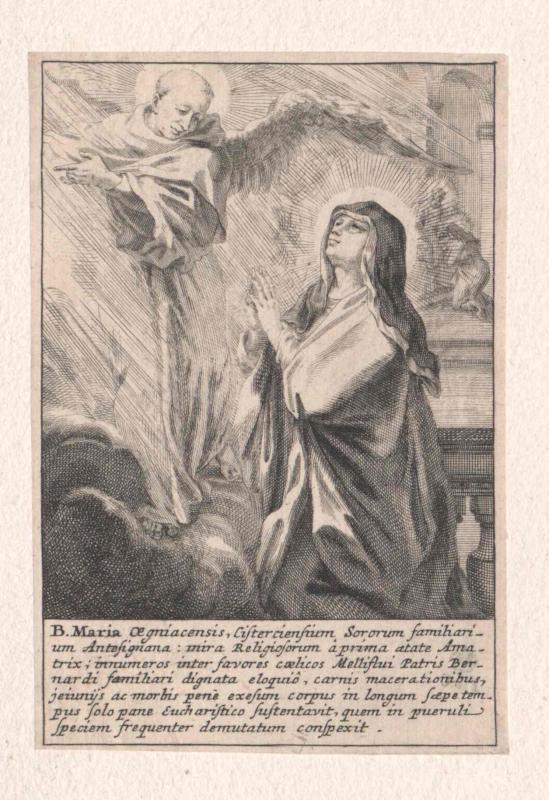

Portrait of Maria von Oignies in Österreichische Nationalbibliothek – Austrian National Library

1600-1700.

https://www.europeana.eu/en/item/92062/BibliographicResource_1000126144459

Most scholars agree that the saint Mary of Oignies, hailing from the diocese of Liège (a district under a specific governance of a bishop), started the first beguinage. James of Vitry, canon of Liège in France, recorded Mary of Oignies’s life. She was prevalent in the later twelfth century. Beguines differed from location to location, yet her story connects them.

Additionally, as the founder her story helped us better understand what was important in beguines’ lives across Europe. According to Neel Carol’s article on the “Origins of Beguines,” Mary was married at fourteen; however, with aspirations of holiness, the young woman convinced her young husband to join her in dedicating herself to “chastity and charity” (327). Beguines are noted for being widowed women, married women, or simply unmarried women. As a married woman, Mary sets the precedent that allows ultra-religious women to devote themselves to God in beguinages, regardless of their level of chastity or marital status.

William McDonnell outlines in his book, The Beguines and Beghards in Medieval Culture, with Special Emphasis on the Belgian Scene, how Mary of Oignies is noted for carrying a little book for prayers to the Virgin Mary (381). Judith Oliver focuses her research on psalter books (a book similar to Books of Hours) in Liège. Oliver explains how “more psalters were owned by women than men in Liège in the 13th century,” and that “manuscript production flourished in the diocese [of Liège]” (2). This timeline is merely one hundred years after Mary of Oigne’s death, making the relationship between books, Mary, and Liège closer. Therefore, through Oliver and McDonnell’s assertions, we can understand the frequency of books among beguines from the start and their importance in beguine devotion.

Mary of Oignes’s role in hospitals also helps us understand the contents of beguine books and how they were used over the centuries. Carol Neel notes how Mary of Oignies and her husband converted their home into a hospital, where they cared for their community (328). Beguines remained involved in hospitals throughout the centuries, as they took on caretaker roles during the most vital parts of people’s lives – birth and death. Sara Ritchey writes in her article how “‘beguine hospital’ and ‘beguine convent’” became synonymous (42). Elfriede Hulshoff Pol notes that in the first centuries of Leiden University their medical books were kept in the nearby beguinage chapel (441). Whether they used books of hours or psalter hours, understanding how beguines were caretakers helps us understand how they used their books.

As caregivers, beguines utilized their prayer books as a way to care for the sick. Ritchey examines how through a certain psalter book, Liège, Bibliothèque de l’Université MS 431, we can understand how beguines “lent their presence and prayers to births” and how “they also provided care and consolation at the bedsides of the dying”(53). She goes on to explain how many of the prayers in psalters and book of hours alike had the sole purpose of alleviating sickness, and when spoken orally these “delivered prayers issued a collective plea for regeneration, sustenance, and salus” (49). Therefore many of the endings of Latin words would take on gender-less or male-gendered instead of female-gendered endings. The gender change in the endings of certain words meant that the prayer could be said for the person being cared for rather than for the beguine herself.

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung. Le roman de la rose.. c. 1390. Artstor, library.artstor.org/asset/BODLEIAN_10310371573

The role of beguines in caring for others offers insight into the contents we would expect from a beguine-owned book of hours. This would include “medical saints” invoked to help with medical problems; a fellow classmate has researched one specific medical saint that is in the Hargrett Hours, Genevieve; the Hargrett Hours also contains suffrages to Apollonia (the patron of toothaches) and Fiacre (who also helped with some ailments). With this knowledge we know medical saints are not abnormal in a typical layperson’s book, especially Apollonia and Genevieve, so just because there are medical saints in the Hargett Hours, we can not say this means it was owned by a beguine. We can infer that the mix of medical saints and the gendered ending of words could lean us towards beguine ownership, but it’s really not a definitive feature. The Hargrett Hours owner very well could have used these invocations of healer saints in their caretaking capacity, because we have some interesting medical saints. However, the evidence we have is really small and too circumstantial to say a beguine used the Hargrett Hours in a caretaking capacity.

The hagiography of Mary of Oignies assists in our understanding of beguine-owned books beyond just surface level components I discovered last semester. Her life set a precedent for how beguines across Europe used books and why they were prevalent in a beguine’s life. While the information gathered does not give us a sure indication of who may have owned the Hargrett Hours, it helps us contextualize how beguines utilized their books and possibly how the owner of the Hargrett Hours used her book.

Authored by Jordan Stanley

Works Cited

McDonnell, Ernest William. The Beguines and Beghards in Medieval Culture, with Special Emphasis on the Belgian Scene. Octagon Books, 1969. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,shib&db=cat06564a&AN=uga.99152033902959&site=eds-live.

Neel, Carol. “The Origins of the Beguines.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 14.2 (1989): 321-341.

Oliver, Judith. “Devotional Psalters and the Study of Beguine Spirituality.” Vox Benedictina, vol. 10, no. 2, Winter, 1992, pp. 200. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/magazines/devotional-psalters-study-beguine-spirituality/docview/216288749/se-2.

Pol, Elfriede Hulshoff. The First Century of Leiden University Library. Brill Archive, 1975.

Ritchey, Sara. “Caring by the Hours: The Psalter as a Gendered Healthcare Technology.” Gender, Health, and Healing, 1250–1550. Ed. Sharon Strocchia and Sara Ritchey. Amsterdam University Press, 2020. 41–66. Print. https://doi.org/10.1017/9789048544462